the domestic myth

Most of us feel fairly secure about our working lives. We may fret about the trajectory of our career, fantasise about switching to another line of work, or dally with launching a business. But generally we don’t have a problem valuing what we do when we’re at work. Our work life gives us back to ourselves. It integrates us, reflecting back a coherent and enhanced sense of self. We may experience pressure at work, we may even come to enjoy it. However this is because we’ve learned to deal with it, recognising that it gives us an edge that drives us on.

Home life, in contrast, presents us with particular challenges. When we’re at home we feel compelled to care about things – mess, dust bunnies and use-by dates – that in the larger scheme of things we don’t care about. Safe from the pressures of the world, we confront uncomfortable feelings and unmet dreams. Such that when a friend drops in unannounced we immediately fall into apologising for our messy house, or thrown-together meal, in a way that we’d never excuse ourselves at work.

Psychological studies have shown that the experience of being at home, where no-one tells us what to do, is more emotionally demanding than the experience of being at work. This is because at work the expectations on us are relatively clear and our performance is noted. It’s at home, where no routine is binding and every task is voluntary, that we are thrown back on ourselves. If I leave wet laundry in the washing machine for thirty-six hours straight, or fail to clean the shower grouting for a year, no housekeeping inspector will come to the front door and fine me.

This looseness, this freedom to make up our own minds about what is worth doing and not worth doing at home, is oddly challenging. Are we living up to the home life that we want for ourselves, that we dreamed of when we were young? Do we have the energy, come evening, to do the things that make us feel good about being at home – preparing loving food, playing with a pet, picking up a musical instrument, inviting a friend round?

The reality is that while we have high hopes for our home lives, many of us don’t live up to them. Domestic depression is rampant, even though we rarely call it that, much less talk about it. And yet this is what leads us to avoid inviting friends over midweek, telling ourselves that we are too busy to entertain. This is what leads us to put off going through ‘that’ cupboard, half shutting our eyes when we’re forced to open it. This is what causes us to let seedlings wilt in their pots, as if something as defenceless as a plant might incriminate us. This is what turns a small paint job that would make the world of difference to our home into an insurmountable demand that we understandably duck. And we avoid all these things, not because they are beyond us – what is so hard about planting out seedlings or picking up a paint brush? – because of the emotional pressure that we imagine they’ll put us under.

What I’ve come to feel, from my conversations about domesticity so far, is that the reason we think twice before talking freely about home life is that we take it very personally. If only I were better organised, you’ll tell me with a sigh. If only I had a cleaner, another will hint. If only I didn’t have a cleaner, still another will say, eyes big. If only I wasn’t renting and could decorate in my own style, my sister will say before she rings off. If only, I’ll return, suppressing my own sigh, my husband and kids were more willing in the kitchen. If only our particular problems could be solved, in other words, our domestic life would feel the way we would like it to feel – casual, chic and smooth. Rather than the loopy chaos that we so often experience it as.

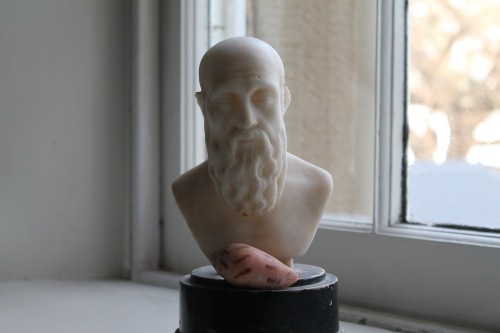

Unlike the beauty myth, which most of us have toppled to, the domestic myth lives on in the nether regions of our minds, in a place where sympathy and understanding rarely reach. This may explain why, once we do talk openly about our home life, shining a light into these nether regions, the domestic myth soon collapses. There is, we discover, no Old Testament figure with beard and pointed finger who scorns our attempts to keep our home life on track. Once this happens, once we realise that our struggle with the laundry basket is shared, we gain a valuable perspective. We stop apologising for our messy house. The overflowing laundry basket no longer sparks embarrassment. Fear of judgment loses its sting when we accept that, like everyone else, we are simply doing our best to keep the dust at bay.

Instead lightness, even laughter, accompanies our efforts to look after our homes. It’s not just me. It’s not just you. There is no woman alive who scrubs her grouting, unclutters her cupboards, weeds her garden, shines cutlery, composts waste, changes fuses and perfects shortcrust pastry. All of us have better things to do than ensure that our saucepans never ever boil dry.

Besides there is a flip side, which is that most of us feel quiet pride in some aspect of our domestic lives. I might sew a garment in a weekend. A friend might fuss over cooking for friends and be pleased when her tart is appreciated. My sister might iron pillow cases, scent them with lavender, and give thanks to a life in which she can do this. It’s these small things, so often the important things, that stand in need of celebration – and that stand to get lost when we button up about home life.

Clearly men too housekeep. They too have cause to celebrate at home. Caring about our things and our spaces, loving them enough to maintain them over time, is an impulse shared by many. However without wanting to go deeply into gender bias, it’s my observation that women experience housekeeping in a very personal way. Keeping the bathroom basin clean is on the same continuum as blowing our nose when we’ve got a cold – and ensuring there are enough tissues in the cupboard when we do. Obviously men look after themselves and buy tissues too, however women feel this connection particularly acutely, and often unconsciously. While I’m loathe to reinforce gender stereotypes, I am seeking to understand women’s experience of domesticity with enough sensitivity and understanding that this area of our lives becomes more interesting to us, more open to change – and even liberation.

There is a lot more pleasure to be had at home than many of us think. We really can dream big domestic dreams and realise them. We can stuff mushrooms, go through our cupboards and win the war on stuff. It is possible to make demands on our home life which don’t then overwhelm us. And one important way to bring this about, which has somehow got left behind with the race for career advancement at the cost of domestic resilience, is by talking about our home life more openly. We really don’t have to solve all the challenges that we meet at home. Much of the answer lies in our willingness to talk about them.

One thread that runs through the twenty-five conversations I’ve had so far, each riveting in its way, is that none of us experiences our home life in the same way. How and why we do what we do at home is deeply revealing of what we care about most in life. It reflects our soul, our heart’s desire. ‘Know me, come to my home’, may not compel as a feminist statement, but it holds true for every woman I’ve spoken with.